Explore & Play

Discover interesting topics and solve the accompanying crossword puzzle.

Art Crossword | Art Styles and Movements

Table of Contents

Welcome to our Art crossword! Feel free to start by testing your knowledge with the crossword, or if you’re not yet familiar with the topic, you can read the article first to gain some insights and then return to the crossword. Either way, this journey through art styles will be both fun and educational!

Art Crossword

You can either fill in the crossword puzzle directly on this page or click the button in the bottom right corner to print it for free.

A Journey Through the History of Art Styles: From Renaissance to Hyperrealism

Art is a mirror of human creativity, reflecting our history, culture, and emotions through various styles and movements. Each era brings a unique perspective, weaving a tapestry of innovation, tradition, and expression. In this article, we’ll embark on a journey through 40 art styles that shaped the visual arts. Along the way, test your knowledge with our crossword puzzle designed to challenge and inspire your artistic curiosity!

The Birth of Art Movements: A Look at Classical Beginnings

Renaissance: The Rebirth of Human Beauty

The Renaissance, emerging in 14th-century Italy, marked a dramatic departure from the medieval mindset, embracing a renewed interest in classical antiquity. Humanism, the core philosophy of this period, placed human beings at the center of intellectual and artistic endeavors. The rediscovery of Greek and Roman ideals, particularly their focus on proportion, balance, and the celebration of the human form, shaped the works of Renaissance masters. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo revolutionized the portrayal of the human body, producing lifelike figures that expressed emotion and movement in a way that had never been seen before. In architectural design, figures like Filippo Brunelleschi and Donato Bramante revived classical columns, arches, and domes, setting the foundation for Western art and architecture.

The Renaissance was also a time of groundbreaking technical advancements. Artists began using oil paints, which allowed for more vibrant colors and greater detail. The creation of linear perspective, particularly by Filippo Brunelleschi, revolutionized the way artists depicted three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional canvas, creating depth and realism that were previously unimaginable.

Baroque: Drama in Light and Shadow

As the Renaissance gave way to the Baroque period in the 17th century, artists moved away from the serene, balanced compositions of their predecessors toward more dramatic and emotional expressions. The Baroque era, which coincided with the Counter-Reformation, was heavily influenced by the Catholic Church’s desire to inspire awe and devotion through art. The works of Baroque artists like Caravaggio, Peter Paul Rubens, and Rembrandt introduced intense realism, dynamic movement, and theatrical lighting that conveyed powerful narratives.

One of the defining characteristics of Baroque art is the use of chiaroscuro, the contrast between light and dark to create a sense of drama and depth. Caravaggio’s “The Calling of Saint Matthew” exemplifies this technique, using stark contrasts of light to focus the viewer’s attention on the pivotal moment in the story. This style, which emphasized the emotional intensity of religious or mythological subjects, was perfect for the dramatic, larger-than-life themes of the time.

In architecture, Baroque design evolved into grand, sweeping forms. Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s work on St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, with its majestic columns and ornate details, embodied the Baroque’s emphasis on grandeur and spectacle. The period also saw the rise of dramatic interior spaces that sought to envelop the viewer, such as the complex designs of the Palace of Versailles in France.

Mannerism: Exaggeration Meets Elegance

After the High Renaissance, a new artistic style emerged that broke with the idealized harmony of earlier works. Known as Mannerism, this movement flourished in the late 16th century and is characterized by its exaggerated proportions, elongated forms, and complex compositions. Artists like El Greco and Parmigianino challenged the calm, balanced beauty of Renaissance art, instead focusing on tension, distortion, and an emotional intensity that evoked a sense of unease.

Mannerist works often distorted the human figure—elongating limbs and torsos in ways that emphasized grace and elegance but at the expense of anatomical accuracy. These figures were not intended to be lifelike, but rather to express spiritual or emotional turmoil. The elongation of form, the twisting poses, and the dramatic use of color made Mannerism a striking and distinct departure from its predecessors.

While Mannerism was often seen as a reaction to the idealism of the Renaissance, it also laid the groundwork for the Baroque period, foreshadowing the emotive power and dynamism that would later define Baroque art.

The Age of Elegance: From Rococo to Romanticism

Rococo: Playful Sophistication

Rococo emerged in the early 18th century as a response to the grandeur and seriousness of Baroque art. It is characterized by its lightness, delicacy, and ornate style, often featuring pastel colors, elaborate curves, and intricate details. Rococo was not just an artistic movement but a cultural one, associated with the aristocracy and their pursuit of pleasure and leisure. The works of French artists like François Boucher and Jean-Honoré Fragonard embodied the spirit of the time—playful, flirtatious, and full of sensuality.

Rococo paintings often depicted scenes of love, mythology, and playful gatherings. The style’s emphasis on intimacy and frivolity was evident in works such as Fragonard’s “The Swing,” where an air of playful abandon and youthful romance took center stage. Rococo interiors, designed to evoke a sense of comfort and elegance, were equally lavish, featuring intricate woodwork, gilded mirrors, and delicate porcelain.

However, while Rococo was initially a symbol of aristocratic wealth and extravagance, it eventually came under criticism for its perceived frivolity and excess. The movement’s eventual decline paved the way for a return to order and simplicity, leading to the rise of Neoclassicism.

Neoclassicism: Order and Harmony Return

In the late 18th century, Neoclassicism arose as a direct reaction to the excesses of Rococo. The Neoclassical movement, inspired by the classical art and architecture of ancient Greece and Rome, emphasized order, rationality, and simplicity. Artists like Jacques-Louis David and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres sought to revive the grandeur and stoic virtues of antiquity, often focusing on heroic subjects, such as historical figures, mythology, and civic virtues.

Neoclassical works were marked by clear lines, restrained emotions, and an adherence to idealized forms. David’s famous painting “The Oath of the Horatii” exemplifies these qualities, portraying a heroic moment from Roman history with sharp lines and a sense of solemnity. Neoclassicism also had a profound impact on architecture, with its symmetrical designs, columns, and domes, seen in iconic buildings like the Panthéon in Paris.

Neoclassicism was more than just an aesthetic choice—it reflected the ideals of the Enlightenment, with its focus on reason, moral integrity, and civic responsibility.

Romanticism: Nature and Emotion Take Center Stage

Romanticism was a dramatic shift from the rationality of Neoclassicism, focusing instead on emotion, nature, and the sublime. Romantic artists, poets, and philosophers rejected the confines of rational thought, instead embracing the power of imagination, intuition, and individual expression. The movement emerged in the late 18th century and reached its peak in the 19th century, with artists like Caspar David Friedrich, Eugène Delacroix, and J.M.W. Turner leading the charge.

Romanticism sought to capture the raw emotion of the human experience, often depicting scenes of intense drama, tragedy, or awe. Caspar David Friedrich’s “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” exemplifies this yearning for transcendence, portraying a solitary figure standing on a rocky precipice, gazing out over a mist-filled landscape. In contrast to the ordered and idealized forms of Neoclassicism, Romantic art often featured sweeping landscapes, turbulent skies, and turbulent seas—symbols of nature’s uncontrollable power and beauty.

In addition to its celebration of nature, Romanticism also championed the artist’s inner vision, personal freedom, and the exploration of the human soul. The movement had a profound influence not only on visual art but also on literature, music, and philosophy, shaping the cultural landscape of the 19th century.

Art Revolution: The 19th Century Transformation

Realism: Everyday Life on Canvas

The 19th century brought with it a new approach to art that rejected the idealization of the past and embraced the reality of modern life. Realism, which began in France in the mid-19th century, focused on the lives of ordinary people, particularly the working class and peasants. Artists like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet captured everyday scenes in a manner that was both detailed and unromanticized, giving voice to those often ignored by traditional art.

Realism arose as a direct response to the Romantic idealization of nature and emotion. Where the Romantics sought grandeur, the Realists aimed to depict the mundane and the commonplace with honesty and accuracy. Courbet’s “The Stone Breakers” is a prime example, showing two laborers in the midst of hard work, their faces unglamorous and their movements realistic. Realist works were grounded in the social and political realities of their time, often addressing issues of class struggle, poverty, and the human condition.

Realism was also the precursor to later movements like Impressionism, as it introduced the idea of focusing on ordinary subjects and exploring the human experience in a direct, unembellished manner.

Impressionism: Capturing Fleeting Moments

Impressionism was born out of a desire to break free from the constraints of academic painting and the rigid rules of realism. In the 1860s and 1870s, a group of French artists led by Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir began to experiment with new techniques that emphasized light, color, and atmosphere. Rather than focusing on precise details, Impressionists aimed to capture the essence of a scene at a particular moment in time.

Impressionism’s hallmark was its loose brushwork and vivid color palette. The artists painted outdoors (en plein air), seeking to capture the ever-changing effects of natural light on their subjects. Monet’s “Impression, Sunrise” famously gave the movement its name, as the painting captured the soft light of the morning harbor in a way that conveyed a fleeting moment. The Impressionists were interested in the transient qualities of life—light, weather, time—and they sought to portray these elements with freshness and immediacy.

While initially criticized for its unfinished look, Impressionism eventually became one of the most beloved and influential movements in art history, paving the way for modern art in the 20th century.

Breaking the Mold: Early 20th Century Movements

The Birth of Modernism: Challenging Tradition

The early 20th century marked the dawn of Modernism, a period that broke away from the conventions of traditional art, literature, and architecture. Modernism emerged as a response to rapid industrialization, technological advancements, and the aftermath of World War I. Artists, writers, and architects sought new forms of expression, rejecting past ideals and experimenting with new techniques. Modernism embraced innovation, individualism, and abstraction, challenging the status quo in every domain.

In visual art, this revolution was seen in the works of pioneering artists like Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Wassily Kandinsky, who abandoned realistic depictions of the world and instead focused on breaking down subjects into geometric forms and abstract representations. Picasso’s groundbreaking work in Cubism, for example, deconstructed objects into fragmented geometric shapes, showing multiple perspectives simultaneously, and this approach radically changed how we view space, form, and time in art.

At the same time, other movements like Futurism and Dadaism emerged, rejecting the old-world values and embracing chaos, speed, and change. Futurists, inspired by the technological innovations of the time, celebrated motion and mechanization, while the Dadaists sought to challenge logic and reason, creating works that were often nonsensical or absurd. These movements highlighted the disillusionment of the time, fueled by the brutality of war and the uncertainty of modern life.

In architecture, Modernism sought to eliminate ornate decoration and instead focused on function and minimalism. Figures like Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier developed designs based on clean lines, open spaces, and the use of new materials like steel and glass. The iconic Bauhaus school, founded in 1919 in Germany, embodied Modernist ideals, promoting a marriage between art, design, and craftsmanship, with a focus on industrial production and functionality.

Futurism: Embracing Technology and Speed

Futurism was a radical and forward-looking movement that emerged in Italy around 1909, led by artists like Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Balla. Futurism celebrated the energy and dynamism of modern life, particularly the speed and motion brought on by industrialization and technological progress. The movement was inspired by the speed of cars, trains, and airplanes, and artists sought to depict the sense of movement in their work.

Futurist art often portrayed figures and objects in a fragmented, dynamic state, reflecting the idea that everything in the modern world was constantly in motion. This was particularly evident in Boccioni’s sculptures and paintings, which captured the interplay of light, color, and motion in a way that made still life appear alive. Futurism also extended into architecture, with structures designed to reflect speed, motion, and modernity, often incorporating curved forms and sharp angles.

The movement’s radical rejection of the past and its focus on progress, however, led to a controversial legacy, with its ties to the fascist movement in Italy later overshadowing the artistic accomplishments of Futurism.

Beyond Reality: Surrealism, Abstract, and Expressionism

Surrealism: The Power of the Subconscious

Surrealism, which gained prominence in the 1920s, was a movement that sought to explore the unconscious mind and the realm of dreams. Inspired by the psychoanalytic theories of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, Surrealist artists believed that the most truthful and profound forms of expression came from the unconscious, where logic and reason were not in control. Surrealists aimed to challenge the boundaries of reality by tapping into the surreal and irrational aspects of human experience.

Led by figures like Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, and Max Ernst, Surrealism created bizarre, dreamlike imagery that defied logical explanation. Dalí’s iconic “The Persistence of Memory,” with its melting clocks draped over trees and branches, is one of the most recognizable Surrealist works. Through such works, Surrealists encouraged viewers to confront the mysteries of the unconscious and to question the nature of reality itself.

Surrealist techniques such as automatic drawing and the exquisite corpse (a collaborative drawing game) allowed artists to bypass rational thought and engage directly with the subconscious mind. The movement influenced not only visual art but also literature, theater, and film, with figures like André Breton and Luis Buñuel exploring similar themes in their writing and cinema.

Abstract Art: Breaking Free from Representation

Abstract art emerged in the early 20th century as a movement that sought to break free from the need to represent the real world. Rather than painting recognizable objects or figures, Abstract artists focused on the use of color, form, and composition to evoke emotions or ideas without reference to the physical world. Wassily Kandinsky, often credited as the first abstract painter, believed that art could convey deep spiritual truths through pure abstraction. His works, such as “Composition VII,” used color and shape as symbolic elements, allowing viewers to engage with the emotional essence of the piece rather than its literal meaning.

In the United States, Abstract Expressionism took hold in the 1940s and 1950s, with artists like Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Willem de Kooning pushing the boundaries of abstraction even further. Pollock’s “drip” paintings, where he splattered or dripped paint onto large canvases, emphasized the physical act of painting as much as the final product, making the process itself an integral part of the work. Meanwhile, Rothko’s vast color fields sought to evoke deep emotional responses, creating an experience that was more about feeling than representation.

Expressionism: Emotion Through Distortion

Expressionism emerged in the early 20th century as a reaction against realism and the idealized forms of earlier art movements. Unlike Surrealism, which focused on the unconscious and irrational, Expressionism was more concerned with portraying raw emotion and subjective experience. Artists like Edvard Munch, Egon Schiele, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner used distorted forms, exaggerated colors, and dramatic brushstrokes to convey intense psychological states and the inner turmoil of the human experience.

One of the most iconic Expressionist works is Munch’s “The Scream,” which uses swirling colors and a distorted figure to evoke feelings of anxiety and existential dread. Expressionism was not limited to painting; it influenced literature, theater, film, and architecture, with artists across disciplines seeking to explore the darker aspects of human nature and to express profound emotional truths.

Expressionism eventually evolved into different subgenres, including Die Brücke (The Bridge) and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), each exploring different facets of emotion and abstraction. The movement would go on to influence many other 20th-century art forms, including Abstract Expressionism and even pop art.

Modernism and Functionality: Bauhaus and Beyond

The Bauhaus: Merging Art with Function

The Bauhaus was an innovative design school founded in Germany in 1919 by architect Walter Gropius. It became a key influence on modern architecture, design, and art by promoting a philosophy that merged art with functionality. The school emphasized the importance of creating objects and buildings that were not only aesthetically pleasing but also practical and efficient. Bauhaus students and teachers—including designers like Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe—believed that art and design should serve the needs of society, focusing on clean lines, simplicity, and mass production.

Bauhaus architecture embraced minimalist design, with an emphasis on geometric forms, open spaces, and the use of modern materials like steel and glass. The Bauhaus school’s impact on modernist design is still evident today in everything from furniture to urban planning.

Beyond architecture, the Bauhaus approach influenced graphic design, textiles, and industrial design. The school’s emphasis on functional beauty, alongside its commitment to education and social responsibility, made it one of the most important movements in 20th-century art and design.

Minimalism: Emphasizing Simplicity

Following the Bauhaus movement and Modernist principles, Minimalism emerged as a reaction against the complexity and excess of earlier art movements. Minimalism emphasized simplicity, with artists stripping away any non-essential elements in favor of clean lines, geometric shapes, and a focus on materials themselves. Artists like Donald Judd, Frank Stella, and Dan Flavin created works that were often devoid of emotion or narrative, focusing purely on form and structure.

In architecture, Minimalism is characterized by clean, unadorned spaces, often featuring open plans and a focus on natural light. The idea is to create a sense of clarity and tranquility by eliminating distractions and focusing on the fundamental elements of design.

The Minimalist movement was influential not only in art but also in music, theater, and literature, where it encouraged a return to simplicity and an emphasis on the essentials.

Functionality Meets Form in the Mid-Century Modern Movement

The Mid-Century Modern movement, which flourished in the mid-20th century, is closely aligned with the principles of Modernism and Bauhaus, but it placed even more emphasis on functionality and user experience. Architects like Charles and Ray Eames and designers like Arne Jacobsen embraced the idea of creating objects and buildings that were not only aesthetically pleasing but also accessible, practical, and comfortable.

Mid-century modern design was characterized by sleek lines, organic shapes, and a seamless integration of form and function. The movement brought design into the everyday lives of people, with functional furniture pieces, streamlined automobiles, and cutting-edge architecture reflecting the values of a new postwar society.

Embracing Diversity: Cultural and Regional Influences

Globalization and the Fusion of Artistic Traditions

The 20th and 21st centuries saw an unprecedented blending of cultural and regional influences, which enriched the global art landscape. The increasing interconnectedness of the world through travel, trade, and communication allowed artists to break free from geographical and cultural constraints, embracing diverse traditions, materials, and techniques. This fusion of ideas and forms led to a richer, more nuanced artistic environment, where regional styles were incorporated into mainstream global art practices, leading to cross-cultural exchanges that enriched the work of artists worldwide.

One of the key examples of this blending can be seen in the work of African-American artists in the United States during the Harlem Renaissance, which brought African cultural motifs and traditions into the heart of modern American art. Artists like Aaron Douglas and Jacob Lawrence infused their works with elements from African tribal art, while also drawing upon American history and contemporary issues of race and identity. Similarly, the influence of Japanese art on European artists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly Impressionists like Claude Monet and Vincent van Gogh, revolutionized the way Western artists perceived composition, space, and color. The Japanese ukiyo-e prints, with their flat compositions, asymmetry, and bold use of color, became key inspiration for many Post-Impressionist painters.

In contemporary art, artists such as Chinese artist Ai Weiwei and Indian artist Anish Kapoor explore their cultural backgrounds and heritage while engaging with global issues. Ai Weiwei’s installations often reflect on Chinese political and social issues, incorporating traditional Chinese techniques and materials in contemporary, thought-provoking ways. Kapoor, originally from India, merges Indian heritage with his exploration of space, form, and materials to create monumental sculptures that engage with both Western and Eastern traditions, offering a powerful commentary on identity, culture, and history.

Indigenous Art: A Dialogue Between Tradition and Modernity

Indigenous art has played a crucial role in shaping the contemporary art scene by offering an alternative perspective grounded in deep cultural traditions. In regions such as Australia, Africa, and the Americas, indigenous artists have fused traditional artistic methods with modern techniques, producing works that are both rooted in their heritage and reflective of contemporary themes.

Australian Aboriginal art is one of the most recognized examples of indigenous artistry, with its intricate dot paintings and symbolic use of color and shapes that tell stories of Dreamtime, the creation myths of the Aboriginal people. Artists like Emily Kame Kngwarreye and Rover Thomas brought this ancient form of storytelling to the global stage, blending spiritual narratives with modern artistic expression. Similarly, Native American artists such as Jaune Quick-to-See Smith use their art to explore themes of cultural survival, colonization, and identity, blending traditional symbolism with modern media to create powerful commentary on the indigenous experience in contemporary society.

As the art world continues to embrace diversity, the voices of indigenous artists contribute to a richer, more complex global conversation, reminding us of the deep-rooted traditions that inform art in every culture.

Photographic Precision: Hyperrealism and Photorealism

The Rise of Hyperrealism: From Photography to Painting

Hyperrealism is a contemporary art movement that pushes the boundaries of realism, seeking to create artworks that are so detailed and accurate that they resemble high-resolution photographs. While photorealism, which emerged in the late 1960s, focused on replicating the precision of photographs through painting or drawing, hyperrealism goes even further by incorporating elements of narrative, emotion, and texture, turning a simple photograph into a work of art that transcends mere replication.

One of the defining characteristics of hyperrealism is the meticulous attention to detail, with artists spending countless hours perfecting every inch of their work. The result is often a stunningly lifelike depiction of subjects, whether it’s a portrait, a landscape, or even an inanimate object. American artist Chuck Close, known for his large-scale portrait paintings, often created works that looked like photographs from a distance but revealed their true complexity and human touch upon closer inspection. Close’s use of grids to replicate the exact detail of his subjects’ faces, down to the smallest pore or wrinkle, brought a new level of intimacy and complexity to hyperrealist art.

Other hyperrealist artists, such as the Italian duo Guido Daniele and the American Robert Bechtle, extend the boundaries of photorealism to create lifelike depictions of people, animals, and still life scenes with remarkable attention to detail. Bechtle’s iconic suburban car scenes, for example, elevate everyday objects into pieces of high art by focusing on their photographic detail and meticulous craftsmanship.

The Emotional Impact of Photorealism

Photorealism is not just about technical mastery; it also captures the nuances of human emotion and experience. While early photorealist works often depicted static objects like cars or street scenes, later works began to include portraits and figures, emphasizing not just the likeness of the subject, but also their personality and emotional depth. Artists like Richard Estes, whose cityscapes of reflective surfaces and bustling streets mirror a sense of modern life, and Audrey Flack, who portrayed everyday objects in stunning detail, elevate the simple into the extraordinary.

One example of this emotional depth is the work of Canadian artist Robert Gober, whose hyperrealist sculptures of everyday items—such as sinks, doors, and body parts—bring a heightened sense of the mundane, transforming ordinary objects into works that evoke feelings of discomfort, nostalgia, or longing. Hyperrealism’s ability to evoke emotion through precision has made it an increasingly popular genre in contemporary art, engaging viewers on both a visual and emotional level.

Optical Illusions and Unique Forms

Op Art: The Art of Illusion

Op Art (short for Optical Art) is a movement that emerged in the 1960s and is dedicated to the exploration of visual perception and illusions. The movement focuses on creating effects that deceive the eye, using shapes, colors, and patterns to produce the illusion of movement or 3D space on a flat surface. Op artists use geometric forms and contrasting colors to create images that seem to pulse, vibrate, or shift as the viewer moves, giving the impression of motion or depth where none exists.

The works of artists like Bridget Riley and Victor Vasarely are prime examples of Op Art, with their mesmerizing patterns that challenge our visual perception. Riley’s “Movement in Squares,” for instance, uses black and white squares arranged in a way that makes the surface appear to ripple, as though the viewer is looking at a 3D surface instead of a flat canvas. Similarly, Vasarely’s iconic “Zebra” creates a hypnotic, dynamic effect using simple shapes and black-and-white contrasts that create the illusion of a fluid, swirling pattern.

The effectiveness of Op Art relies on the manipulation of visual perception and the way our brains process color and form, creating a truly interactive experience between the artwork and the viewer. These pieces demand active engagement, inviting the audience to shift their perspective and immerse themselves in the optical illusions.

Kinetic Art: Art That Moves

Kinetic Art takes the concept of optical illusions one step further by introducing actual movement into the artwork. The movement can be mechanical, powered by motors or other devices, or it can rely on the interaction of the viewer to activate the piece. Kinetic artists, including Alexander Calder, Jean Tinguely, and Len Lye, explored the relationship between art and motion, creating works that evolved and transformed over time.

Calder’s “mobiles,” delicate sculptures suspended from wires, create constantly shifting forms as they move with air currents. Tinguely’s “auto-destructive” sculptures, on the other hand, are machines that disassemble themselves, reflecting his fascination with the destruction and creation inherent in the passage of time. Through kinetic art, the boundaries between object and performance, stillness and motion, are blurred, inviting viewers to experience art in a dynamic and participatory way.

In addition to its physical movement, Kinetic Art often engages with light, sound, and mechanical interaction to create multisensory experiences. These works challenge our traditional understanding of art as static and unchanging, offering a new paradigm where art is constantly in flux, encouraging viewers to think about the passage of time and the role of technology in contemporary life.

The Endless Evolution of Art Styles

From Renaissance grandeur to Hyperrealism’s photographic precision, art styles represent humanity’s boundless creativity. These movements continue to inspire modern artists, architects, and designers, proving that art is a timeless language of expression.

Now that you’ve explored these styles, why not challenge yourself? Test your knowledge with our crossword puzzle and dive deeper into the fascinating world of art!

Share to...

I hope you enjoy the content.

Want to receive our daily crossword puzzle or article? Subscribe!

You may also be interested in

Share to…

Want to receive our daily crossword puzzle?

-

Jigsaw Puzzles

Nordkapp Abstract Art Jigsaw Puzzle 250 | 300 | 500 Pieces

kr 348,00 – kr 439,00Price range: kr 348,00 through kr 439,00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Jigsaw Puzzles

Blue-Eyed Kitten Puzzle Delight 250 | 300 | 500 Pieces

kr 348,00 – kr 439,00Price range: kr 348,00 through kr 439,00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

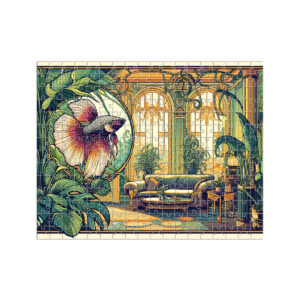

Jigsaw Puzzles

Art Nouveau Jigsaw Puzzle with Betta Fish in Lush Garden Scene 250 | 300 | 500 Pieces

kr 348,00 – kr 439,00Price range: kr 348,00 through kr 439,00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page